California is a greatly exceptional state. Gold-filled Sierras, beautiful cliffsided coasts, rich valley soil, and the most creative populace. I take great pride in being a Californian. I’ve loved exploring and learning about this state’s histories: geologic, economic, and cultural. In fact, a personal goal of mine is to someday catalog all our state’s historical landmark sites.

Until recently there was one part of the puzzle missing from my personal mapping of the state. I was recently afforded a little free time before starting a new job and decided to finally go explore Lassen, Modoc, Shasta, and Siskiyou counties.

The trip started by meeting Ryan in Redding. We parked his car by the airport and carpooled into Lassen National Park. The air in Redding was muggy and thick with smoke from an active and growing Green Fire just northeast of the city. We were reassured by the air clearing as we climbed up the six thousand or so feet of elevation to the park’s entrance, but a quick stop in Shingletown just before the park’s North entrance made it clear we wouldn’t be entirely free of the fire’s smoke. Rather, wildfire smoke would shadow much of the trip.

We planned to trek up Lassen Peak as our first hike but stopped for the short Devastated Area loop to learn more of the 1915 eruption. 110 years ago in May, Lassen erupted, ravaging the forests of its eastern slope. At eruption, a plume of smoke was visible in Eureka, and the heat of the lava released water from the snowmelt that flooded into Hat Creek Valley towards the Pit River; ash rained as far east as Elko, Nevada. As we continued towards the peak, we saw a fresher devastated area from the 2021 PG&E-caused Dixie Fire, which burned through much of the park. While these events wrought the landscape when they occurred, new growth is clearly well underway.

Following our hiking and camping in the park, we headed back north up 89 towards Lava Beds National Monument in Modoc County. We stopped at McArthur–Burney Falls Memorial SP to see the water fall that feeds into the Pit River. The park was full of PCT hikers refreshing their water stashes and enjoying the cool mist of the falls. During the drive I was struck by all the logging activity and free-range cows. It was odd to see an area recently clearcut, likely then grazed, with new growth trees planted all in neat, orderly rows juxtaposed against more naturally formed forest. During the drive we saw the Fall River and aforementioned Hat Creek and Pit rivers, which all flow into the Sacramento River.

The lava tube caves we aimed to explore formed when the Medicine Lake Volcano erupted. Mount Shasta, the Medicine Lake Volcano, and Lassen Peak are all three the California volcanoes which make up the Cascade Volcanic Arc, which includes Mount Rainier, Saint Helens, and Crater Lake to name a few. The difference between the Cascade Range and Sierra Nevada mountains is subtle, but noticeable—and our visit proved worthwhile so far.

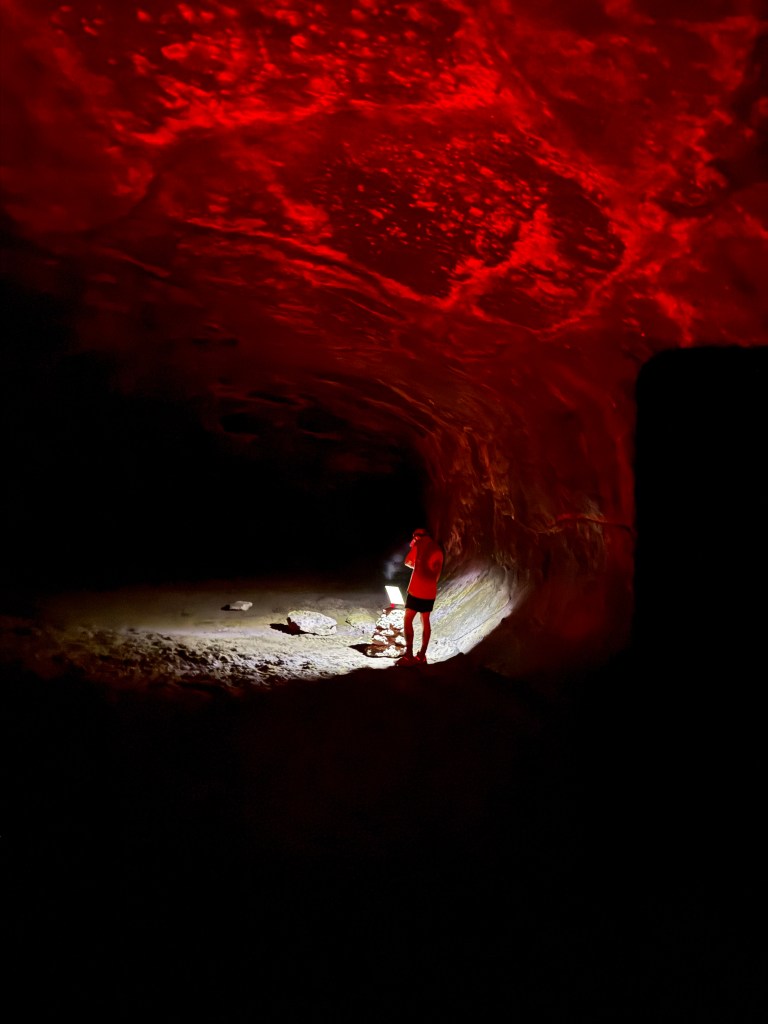

The lava tube caves were great to explore — there’s some childlike curiosity intrinsic in spelunking. Where does the next turn go? Likely nowhere new, but one must check. And the caves were so cool, literally a reprieve from the high 90s heat of the outside. The Skull Cave actually led down to a pool of frozen ice, its inner stone walls cold to the touch. The Symbol Bridge Cave was covered in Native pictographs. We learned the cave was likely a site for vision quests. One can easily see why the Native Americans would revere the landscape. The lava fields felt surreal and martin on their own. And they would eventually serve as a stronghold for the Modoc Indians during their 1872 battle with US forces. Clearly the Modocs knew their land well.

We camped at the monument. Compared to the treed mountains of Lassen, the Lava Beds monument was vast and open. Perhaps our best air quality on the trip, we took advantage of the clear sky for some stargazing. But from the plateau of our campsite we could see smoke rising in Southern Oregon. We felt flanked by fires, and hoped that the smoke would be clearer when we headed back Southwest the next day.

The trip practiced my father’s “Circle theory,” never travel to and from in a line, but circle the trip to see more. So we rounded out the trip by circling back towards Redding, and staying north outside of Shasta; camping on the McCloud River. From there we could fish and chat with conservationists working to reintroduce salmon to the river. And Ryan caught his first trout on a fly rod! We spent a little time exploring and dining in the towns of McCloud, Dunsmuir, and Mount Shasta, meeting slow to start PCT through-hikers and local fishing legends at Ted Fay’s fly fishing shop. We fished, with little success, the upper Sacramento River in Castle Crags State Park. But I’m eager to return for a weekend when the weather cools.

After wrapping up our fishing, Ryan and I headed down the five back into Redding. The further south we went, the wider the Sacramento River grew.

Visiting many of the tributaries of our state’s principal river was not planned, but a happy accident. On countless Tahoe trips I’ve driven over the river on Highway 80 in Sacramento with little regard.

But in reflecting on the trip I’m reminded of John Muir’s famous quote, “When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe” from My First Summer in the Sierras. What I thought was just filling in a missing puzzle piece, exploring those northern counties, revealed itself as something far richer. Fires and logging giving way to new growth, volcanic geothermal springs feeding into the Sacramento and lava flows creating caves for vision quests and spelunking, catching trout and restoring salmon. My starting a new job had afforded me the time to fit in this last piece, but in doing so, I discovered that the whole of California’s story is infinitely more complex and beautiful than the sum of its parts.

Leave a comment